The Davidic Psalter

This article originally appeared on Fish Eaters and is being used under Section 107 of the Copyright Act. It is for non-profit use to bring about the Triumph of the Immaculate Heart into the world. If you have any questions please contact info@livefatima.io.

(Note that this page uses the Greek — LXX, Vulgate, Douay-Rheims — Psalm numbering system, as does the entire “Being Catholic” section of this site)

And, among all the books, the Psalter has certainly a very special grace, a choiceness of quality well worthy to be pondered; for, besides the characteristics which it shares with others, it has this peculiar marvel of its own, that within it are represented and portrayed in all their great variety the movements of the human soul. It is like a picture, in which you see yourself portrayed, and seeing, may understand and consequently form yourself upon the pattern given. Elsewhere in the Bible you read only that the Law commands this or that to be done, you listen to the Prophets to learn about the Saviour’s coming, or you turn to the historical books to learn the doings of the kings and holy men; but in the Psalter, besides all these things, you learn about yourself. You find depicted in it all the movements of your soul, all its changes, its ups and downs, its failures and recoveries.What did these soulful songs sound like when they were sung at Temple and in synagogues — even by Jesus and His Apostles? Like the mother to Gregorian and Byzantine chant, which spring from Old Testament chant that is at least 3,000 years old. Consider: when our Lord recounted the Hallel as He instituted the Eucharist, He most likely would have sounded much like our priests do today. Our Hebrew forebears chanted the Psalms, even as we do now, both responsively (groups chanting alternating verses) and antiphonally (with repetition of the first verse).

Organizing the Psalms

The 150 Psalms that make up the Psalter are often grouped into five Books, like and related to the five Books of Torah (the first five books of the Bible, also known as the Pentateuch), each of which may be described as having an historical relevance:

Book I | 1-40. Doxology: Psalm 40:14 | Genesis David’s conflict with Saul |

Book II | 41-71. Doxology Psalm 71:18-20 | Exodus David’s Kingship |

Book III | 72-88. Doxology: Psalm 88:53 | Leviticus The Assyrian Crisis |

Book IV | 89-105. Doxology: Psalm 105:48 | Numbers Destruction of the Temple and Exile |

Book V | 106-150. No doxology | Deuteronomy Praise and the New Era |

Aquinas rejected the idea of their being grouped into 5 Books, mentioning in his “Commentary on the Psalms” that others see the Psalms grouped into perfect thirds:

The third distinction is that the Psalms are distinguished into three groups of fifty: and this distinction takes in the three fold state of the faithful people: namely the state of penitence; and to this the first fifty are ordered, which conclude in Have mercy on me, O God, which is the Psalm of penitence. The second concerns justice, and this consists in judgement, and concludes in Psalm 100, “Mercy, and justice.” The third concludes the praise of eternal glory, and so it ends with “Let every spirit praise the Lord.”

The point is that they can be grouped in many different ways, by theme or poetic style. For example:

Wisdom Psalms | 35, 36, 48, 72, 111, 126, 127, 132 |

Royal Psalms | 2, 18, 20, 21, 45, 72, 101, 110, 144 |

Laments | Individual: 3, 21, 30, 38, 41, 56, 70, 119, 138, 141 |

| Corporate: 2, 44, 80, 94, 137 2, 43, 79, 93, 136 | |

Thanksgiving | Individual: 17, 29, 31, 33, 39, 65, 91, 114, 115, 117, 137 |

| Corporate: 64, 66, 74, 106, 123, 135 | |

Enthronement | 23, 28, 46, 92, 94-98 |

Praise | 8, 18, 32, 66, 99, 102, 103 , 110, 113, 116, 144-148 |

Acrostics | 9, 24, 33, 36, 110, 111, 118, 144 |

Grouping by Liturgical Use

The Psalms are grouped by their liturgical use, too. The ancient Hebrews chanted Psalms 119 to 133 (known as the “Gradual Psalms,” “Songs of Ascent,” “Songs of Degrees,” or “Pilgrim Songs”) when travelling to Jerusalem to celebrate Passover and the Feast of Unleavened Bread in the Spring; Pentecost in Summer; and the Atonement and Tabernacles in Fall. Psalms 112 to 117 are known as “Hallel” (also the “Common Hallel” or “Egyptian Hallel”) and are chanted on Passover night, Pentecost, the Feast of the Unleavened Bread and the Feast of Booths.

According to the Jewish Encyclopedia’s view, the Talmud states that:

…psalms were sung by the Levites immediately after the daily libation of wine; and every liturgical psalm was sung in three parts (Suk. iv. 5). During the intervals between the parts the sons of Aaron blew three different blasts on the trumpet (Tamid vii. 3). The daily psalms are named in the order in which they were recited: on Sunday, xxiv.; Monday, xlviii.; Tuesday, lxxxii.; Wednesday, xciv.; Thursday, lxxxi.; Friday, xciii.; and Sabbath, xcii. (Tamid l.c.).

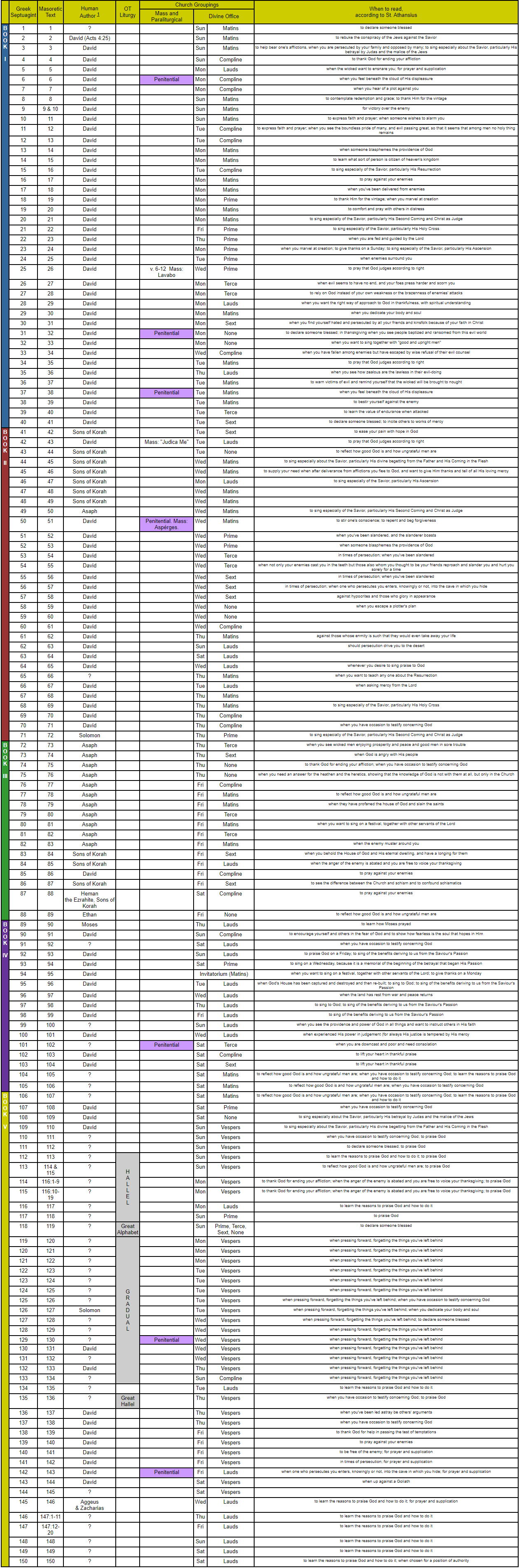

This is precisely how the Church groups Psalms for the Divine Office (see table below) — based on the day of the week, but with the Psalms spread out throughout the week such that, in a week’s time, the entire Psalter is prayed (Psalm 94 — the Invitatorium — is prayed each day as the opening prayer of the Office).

Another Christian grouping of Psalms are those seven called “Penitential” — Psalms 6, 31, 37, 50, 101, 129, 142. These Psalms — among them are the “Miserére” (Ps. 50) and the “De Profundis” (Ps. 129) — are recited during Lent by order of Innocent III (A.D. 1198-1216). St. Augustine (d. A.D. 430) was so taken by these beautiful Psalms that he asked that a monk write them in large letters near his bed so he could read them as he lay dying.

And, of course, the Psalms fill the Mass, both in its Ordinary and Propers. The Júdica Me (Ps. 42) opens the Mass, the Aspérges consists of parts of Ps. 50, at the Lavabo we hear Psalm 25:6-12, the Introit and Gradual (and sometimes the Offertory and Communion prayers) are Psalms, etc.

For a plan to read the entire Psalter, you can read them according to the schedule used in the Divine Office, starting each day’s readings with Psalm 94. For inspiration, read the rest of St. Athanasius’s letter here, in which he tells his friend, Marcellinus, of the beauty and usefulness of the Davidic Psalter.

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, a Decree of the Biblical Commission of 1 May, 1910 “affirms that aside from those Psalms explicitly attributed to David elsewhere in the Bible, the authorship [of unattributed Psalms] by David cannot be magisterially affirmed or denied.” Note that the old Biblical Commission was considered magisterial; the present Commission is not, as is admitted to by Cardinal Ratzinger, who clearly states in a preface to the 1994 document “The Interpretation of the Bible in the Church” that the “Pontifical Biblical Commission, in its new form after the Second Vatican Council, is not an organ of the teaching office…”